Cover image of the White House after President Gardfield’s death. (Courtesy of Billion Graves)

A major theme in my new novel, Shores of Chaos: Darkness Follows, is death. The societal customs and industry that accompanied death changed dramatically in the Victorian period. Prior to this period and during the early part of it, it was the general practice for the dead to be prepared in their homes by family members or specialized members of the community.1 A physician likely determined death by using less than scientific methods such as placing a mirror by the nostrils or using a pin to prick the body.2 The wake would be held in the home’s parlor before the procession to the church and cemetery.1 Bodies were wrapped in a shroud or placed in a wood coffin and buried at the church’s graveyard if they were not buried on the family’s property.2 Early coffin and casket makers were primarily furniture makers. When they later offered to undertake services such as preparing the body or digging the grave they became known as “undertakers.”1

Preparation of the body changed during the Civil War when embalming took off as families wanted the bodies of their loved ones returned home, which often meant the deceased would be travelling over long distances.1 As the practice grew, embalming could be done at home with a travelling embalming kit.2 Likewise, the first crematorium was built in the United States in 1876 and cremation gained traction over the years.3 Those that still used home wakes could have their houses built with specially made doors to remove the coffin or casket and take it directly to the street.4 During the Victorian period, undertakers also started to change their names to the more professional-sounding mortician and funeral director. They made designated buildings for funerals or turned their own homes into professional parlors. Viewings that once used to be held in the home parlor moved to funeral parlors, and the home parlor became known as the living room to lose the connotations with death.1 Prior to the use of automobiles, the dead would be moved on a horse drawn bier and some biers were elaborately decorated with carved images and velvet drapes. The first motorized hearses were produced in the early 1900s.5 In addition, burials moved into newly created, park-like, independently owned cemeteries. Some families would buy a plot with multiple grave spots for several generations and have an iron fence enclosing it with a monument. People were, perhaps rightly so, afraid of being buried alive at this time so special caskets were made that had ropes connecting to bells above the ground. Those working the “graveyard shift” would listen for the bells. 2

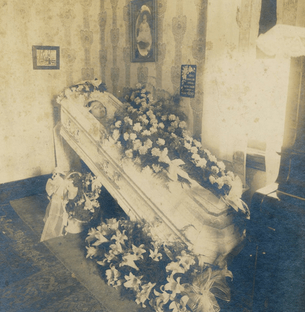

When a person died, the Victorians took on many customs and rituals. The home was draped with black crape and a black wreath was placed on the front door to indicate to others that the household was in mourning and to pass by the home quietly out of respect.4,6 Wreaths with white flowers or white swags above the door were used to indicate children had died. Mirrors were covered to prevent the deceased’s spirit from getting stuck in them. Clocks were stopped, both for accurate reports of the time of death and out of respect for the person’s passing.4 Family members would offer funeral cookies or biscuits that would be wrapped in paper and sealed with black wax. The coffin or casket would be decorated with flowers, partly used to hide the scent of decay.6 The flowers sent by friends and relatives often had particular meanings so that one could relay their emotions without speaking. For example, tulips meant friendship, pink carnations were for never forgetting, and zinnias were for lasting affection. Families would also take photos of the dead, sometimes posing with them. Often these photos were the only ones taken of the deceased in their life.4 Family members would make mourning brooches or other jewelry that could include a photograph of the deceased or even a lock of hair.3,6 Hair would also be made into elaborate arrangements such as wreaths and hair would be added to the arrangement over the years as more family members passed over.4

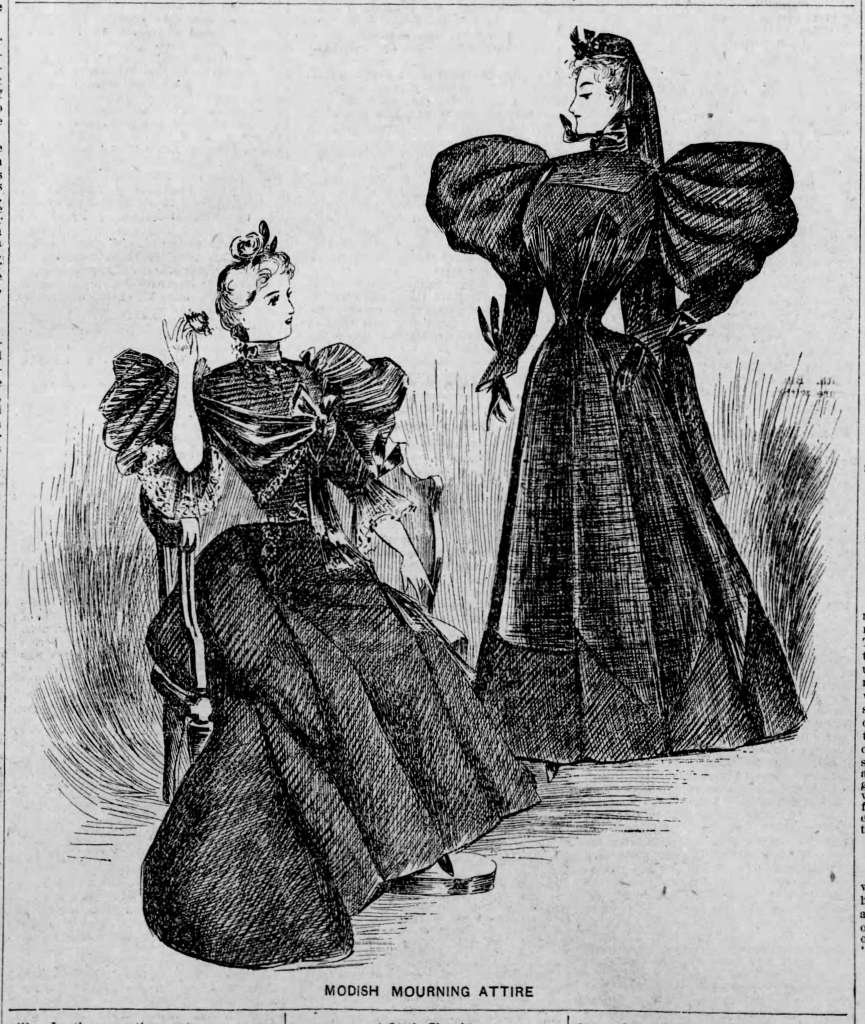

Perhaps the most recognizable image of Victorian mourning was the donning of all black clothing. Queen Victoria influenced the greater population to wear black for mourning when her husband Prince Albert died in 1861 as she would wear black for the rest of her life.6 Mourning dress was dictated by etiquette and those of the upper classes followed it more strictly than others to show both their breeding and social position as well as their grief. Mourning was expected to happen in stages to show how deeply grief stricken a person was. The first stage of mourning dress was deep mourning with black attire made of lusterless fabrics like crape or wool and minimal ornamentation. The second stage was ordinary mourning and women were allowed to wear shinier gowns with more ornamentation and simple jewelry. The last stage was half-mourning and allowed for grays, purples, and white. Mourning dress was expected to last from months to years depending on one’s relationship to the deceased. Widows were expected to be in deep mourning for at least a year while siblings need only be in mourning for six months. Widowers were expected to be in mourning for six months and would sometimes wear a black armband or hatband. Young children were often not expected to wear black as it was believed it would dampen their spirits. Instead, they could be dressed in white with black trimmings. Not everyone could afford an entire new black wardrobe when someone died, so they either dyed old clothing or had one set of clothes designated for the occasion. By the early 1900s, many had grown tired of the strict rules for mourning and wanted to not call attention to the fact that they were grieving. As a result, mourning dress became more designated by one’s personal preference than societal expectations.7

So what do you think of the Victorians and how they mourned the dead? Do you think we should still follow some of these traditions? Or do you prefer our modern way of mourning? Share your thoughts below.

Sources

- “Funeral homes in the 1800s” by MayFuneral. Aug. 23, 2016. https://blog.htmayfuneralhome.com/2016/08/funeral-homes/

- “Burial Customs Differed at the Turn-of-the-Century” by Wendy Chestnut. Apr. 16, 2018. https://www.sungazette.com/news/top-news/2018/04/burial-customs-differed-at-turn-of-the-century/

- These 17 Photos Show how much the Funeral Service has Changed in the Last 150 years” by Rochelle Rietow. Dec. 3, 2014. https://blog.funeralone.com/industry-trends/history-funeral-homes-photos/

- “Preparing the Victorian Home for a Funeral” by Cathy Wallace. 2021. https://blog.billiongraves.com/preparing-the-victorian-home-for-a-funeral/

- “Driving the Dead, A History of the Hearse” by Rachel Osolen. Sept. 22, 2021. https://www.talkdeath.com/driving-the-dead-a-history-of-the-hearse/

- “Gone but Not Forgotten: Victorian Mourning & Funeral Exhibit at Hearthside House” by The History List. 2016. https://www.thehistorylist.com/events/gone-but-not-forgotten-victorian-mourning-funeral-exhibit-at-hearthside-house-lincoln-rhode-island

- “Memory and Mourning: Death in the Gilded Age” by Dawn Reid Brean. Sept. 19, 2019. https://www.thefrickpittsburgh.org/Story-Memory-and-Mourning-Death-in-the-Gilded-Age